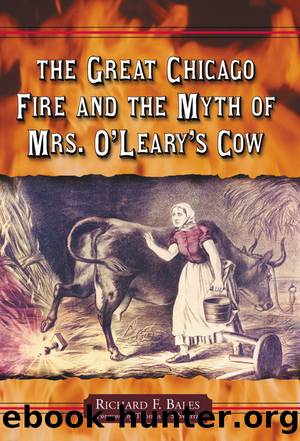

The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow by Richard F. Bales

Author:Richard F. Bales

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Published: 2013-05-01T00:00:00+00:00

Were the Firemen Intoxicated As They Fought the Fire?

One of the threads that runs consistently through the pages of the inquiry transcript is the issue of whether or not the firemen were intoxicated as they fought the fire. This line of questioning was probably not unexpected, with the Evening Journal reporting as early as October 24 in an article entitled âLiquor-Drinking Firemenâ that âthere seems to be no question that a fire department, strictly trained to abstinence, would have saved our city as easily on Sunday night as on Saturday. The temptation which Saturdayâs exhaustion and Sundayâs rest brought worked a world of mischief.â Less than a month later, Alfred Sewell echoed this opinion (but more bluntly) in his book The Great Calamity!: âA drunken Fire Department is, in a measure, responsible for the destruction of Chicago.â48

So were Sewell and the Evening Journal correct? Did Chicago burn because its firemen were lit? As expected, the facts are not as clear-cut as Sewell suggests.

Historians Elias Colbert and Everett Chamberlin maintained that in 1871, firemen would celebrate the successful culmination of their firefighting efforts by âa good thorough drunk.â They claimed that because of the firemenâs indulgence after the Saturday night fire at the Lull & Holmes planing mill, the department was not in the best condition for a second bout of fire fighting the following day. Instead, exhausted from work and hung over as well, the men labored âstupidly and listlessly.â49

But if they did appear stupid and listless, it was probably not because of alcohol. Twenty-seven firemen testified at the inquiry. Ten of them indicated what time it was when they finally finished working at the Lull & Holmes fire, which started at about eleven oâclock Saturday night. All ten worked throughout the night, and seven men did not leave the planing mill until Sunday afternoon. Third Assistant Fire Marshal Mathias Benner testified that âa portion of the department [was] at work there about eighteen hours.â Surely after battling this fire, the men would have been interested in only food and rest, not drink. The transcript of the inquiry certainly bears this out; fireman Leo Meyersâ testimony is typical:

Q.âDid you see any of the firemen or marshals intoxicated?

A.âNo sir.

Q.âDid not visit any engine houses except your own on the Sunday after the Saturday night fire?

A.âNo. We worked around, did not get home until two or three oâclock in the afternoon from the Saturday night fire. The first thing we done, we laid down for a rest until [Box] 28 came in.

Q.âThere has been some charges made of carousing at the engine houses Sunday.

A.âThat is the first I am aware of it.50

But this is not to say that the firemen met the Evening Journalâs standard of a department that was âstrictly trained to abstinence.â James Hildreth testified that he âdrank more than the firemen did,â and at least one fireman, William Mullin, foreman of the steamer Illinois, admitted to drinking on the job. But Mullin was adamant that he knew of no intoxicated firemen:

Q.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32531)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31929)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31919)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31905)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19022)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15898)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14468)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14041)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13831)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13334)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13320)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13218)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9301)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9263)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7482)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7292)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6731)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6602)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6250)